Who Was Jim Thorpe, Native American Athlete And Olympian?

Jim Thorpe (May 28, 1888–March 28, 1953) is remembered as one of the greatest athletes of all time. At the 1912 Olympics, Thorpe accomplished the unprecedented feat of winning gold medals in both the pentathlon and the decathlon. His record-breaking scores beat all of his rivals and remained unbroken for three decades.

Thorpe was born in Prague, Oklahoma, one of 11 children to parents of Native American and European heritage. He grew up in a log farmhouse on the Sac and Fox reservation, where his family grew crops and raised livestock. Even on the reservation, the Thorpes adopted many customs of white people. They wore standard American clothing, spoke English at home, and were Roman Catholics. In 1894 at the age of 6, Jim Thorpe and his twin brother were sent to the reservation boarding school run by the federal government 20 miles away from their home. Indian students were taught to live as white people and were forbidden to speak their native language. Jim Thorpe excelled at all sports. When his twin brother died at age 8, Thorpe ran away from school and back home. When he was 10, his parents sent him to Haskell Indian Junior College in Lawrence, Kansas, which operated on a military system, with students wearing uniforms and following a strict set of regulations.

When he was 13, his father had an accident, and Thorpe ran away from Haskell and returned home to help out. Unfortunately, his mother died a few months later, and not getting along with his father, Thorpe left home and went to Texas where he worked taming wild horses, but he returned home after a year. Then he enrolled in a nearby public school, where he participated in baseball and track and field and again excelled at whatever sport he attempted.

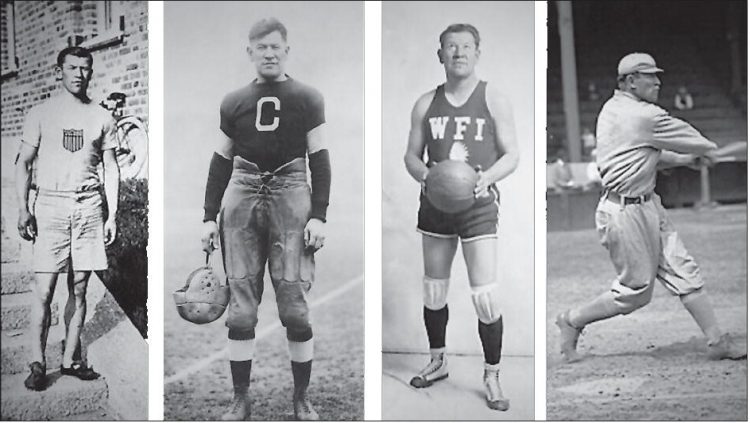

In 1904, when Thorpe was 16, a representative from the Carlisle Indian Industrial School in Pennsylvania came to the Oklahoma Territory looking for American Indian students and enrolled Thorpe in the trade school. Not long after he'd begun his studies, his father died. Thorpe went on to excel in football, baseball, track and lacrosse, and also dominated in hockey, handball, tennis, boxing and ballroom dancing. During his summers at Carlisle, Thorpe was sent to live with white families in order to learn white customs. He earned his way working as a gardener and farm worker. Like other students, to earn money, Thorpe worked two consecutive summers (1910 and 1911) playing minor league baseball in North Carolina.

In the fall of 1911, when Thorpe returned to Carlisle, he earned recognition as a first-team All-American halfback. In 1912, he led Carlisle’s football team to a 12-1-1 record. Encouraged by his coaches, he began training for a spot on the U.S. Olympic team in track and field. Thorpe qualified for both the pentathlon and decathlon for the American team. The 24-year-old American Indian set sail for the Olympics in Stockholm, Sweden, in June 1912.

Although Thorpe’s parents were both half Caucasian, he was raised as a Native American. He accomplished his athletic feats during a period of racial inequality in the United States and most of the world. It has often been suggested that his Olympic medals were stripped by the athletic officials because of his ethnicity. At the continued from page

time Thorpe won his gold medals, not all Native Americans were even recognized as U.S. citizens. Citizenship was not granted to all American Indians until 1924.

At the Olympics, his performance surpassed all expectations. He dominated in both the pentathlon and decathlon, winning gold medals in both events. (He remains the only athlete in history to have done so.) It should be noted that Thorpe dominated the Olympics wearing two shoes of different sizes he found in a trash can (because someone had stolen his track shoes just before the event).

Upon his return to the United States, Thorpe was honored with a ticker-tape parade in New York City. Back home, after a tiring round of parades and celebrations, he returned to the Carlisle Indian Industrial School and led the football team through a triumphant season, culminating in a celebrated victory over Army.

However, in January 1913, a newspaper article claimed that Thorpe had earned money playing professional baseball (the two summers he had played when he was a student) and therefore could not be considered an amateur athlete. Because only amateur athletes could participate in the Olympics at that time, Thorpe’s medals and two other Olympic trophies were taken from his house in his absence and shipped back to Stockholm. The medals themselves reverted to the Scandinavian runners-up in both events. Thorpe’s name was expunged from the record books. His score in the decathlon remained unbeaten but unacknowledged for decades.

Thorpe readily admitted that he had played in the minor leagues and had been paid a small salary, but he didn’t know that playing baseball would make him ineligible to compete in track and field events at the Olympics. Thorpe later learned that many college athletes played on professional teams during the summer, but they used assumed names in order to keep their amateur status in school, whereas he had played under his own name.

When the newspaper scandal broke around Thorpe, many people remained strongly on his side. Many editorials defended him and ridiculed the Amateur Athletics Union (AAU), which was founded in 1888 to establish standards in amateur sports. Although Thorpe himself remained stoic and rarely complained about the loss of his Olympic medals, his friends were furious.

They turned their rage on the Carlisle officials that they felt had failed to defend the school’s greatest star. Gus Welch (Ojibwe), Thorpe’s roommate and best man at his wedding, gathered more than 200 signatures on a student petition urging the Commissioner of Indian Affairs to investigate misconduct in the school’s administration and athletic department. The Bureau of Indian Affairs assigned an investigator who wrote a thoroughly hostile report.

The results were devastating to Carlisle Indian Industrial School. Although the school lincontinued from page

gered on until August 1918, when the Army took it back for war uses, the retraction of Thorpe’s medals was the fatal blow to its existence. Thorpe himself remained loyal to Carlisle, visiting the campus when his work brought him nearby, and even inviting Superintendent Friedman to participate in his wedding. He repressed the hurt of losing the medals and revealed it only in private moments.

In order to support himself, Thorpe left Carlisle and played professional football and baseball. As a major box office draw, he helped put professional football on its feet, serving as first president of the forerunner of the National Football League. He is a main reason pro sports are now so deeply a part of American life.

Later he became a professional coach and motivational speaker for young people. Thorpe struggled to stay employed after leaving professional sports. He moved from state to state, working as a painter, security guard, and ditch digger. He even tried out for some movie roles but was given only a few cameos, mainly playing Indian chiefs.

When the 1932 Olympics came to Los Angeles, Thorpe was living in the city, but he didn’t have enough money to buy a ticket. Vice President Charles Curtis, also of Native American descent, invited Thorpe to join him. When the crowd became aware of Thorpe's presence, he was honored with a standing ovation. In 1951, Thorpe was memorialized in the Warner Bros. movie about his life Jim Thorpe – All-American, which is now on DVD.

Thorpe married three times and had a total of eight children. In 1913, he married Iva M. Miller, whom he had met at Carlisle. They had four children: James F., Gale, Charlotte, and Frances Thorpe. They divorced in 1925. In 1926, Thorpe married Freeda Verona Kirkpatrick, who was working for the manager of the baseball team for which he was playing at the time. They had four sons: Phillip, William, Richard, and John Thorpe. They divorced in 1941, after they had been married for 15 years. Last, in 1945 Thorpe married Patricia Gladys Askew, who was with him when he died.

Over the years Thorpe’s family and friends kept petitioning the International Olympics Committee (IOC) to restore his rightful honors. The campaign intensified after Thorpe suffered a fatal heart attack on March 28, 1953, and died at the age of 64 in Lomita, California. Avery Brundage, who was the president of the IOC from 1952 to 1972 pushed against the campaign to get the medals back to Thorpe. Brundage had an ulterior motive as he had competed against and lost out to Thorpe in the 1912 Olympics in the pentathlon and decathlon.

Brundage has been blamed for everything from stealing Thorpe’s track shoes at Stockholm to reporting his lack of amateur status to the IOC. With Thorpe removed from the winner status, Brundage became the national all-around champion, a standing that helped open doors to his construction business. Brundage retired in 1972, and the next year the AAU voted to reinstate Thorpe’s amateur status.

But the tipping point came when a copy of the rules for the 1912 Olympics was located and shown to state that objections to the qualification of a competitor “must be . . . received by the Swedish Olympic Committee before the lapse of 30 days from the distribution of prizes.” The letter from the AAU in 1913 disqualifying Thorpe had arrived well past the deadline. The retraction of Thorpe’s medals not only was unfair, it was illegal. With this evidence, on October 13, 1982, the IOC voted to restore Thorpe’s honors. However, the original medals had both been stolen from Scandinavian sports museums. So the IOC proposed striking commemorative medallions, rather than Olympic medals. Thorpe’s supporters objected to medallions, and through friends in Sweden located the molds for the original medals. New medals were struck from the original molds, not of gold as Thorpe’s had been since gold had been discontinued for the medals after 1912, but of the modern silver alloy with gold plating. The new medals were presented to Thorpe’s children in Los Angeles in 1983, as part of the build-up to the 1984 Los Angeles Olympics.

Thorpe’s daughters Gail and Grace presented the medals to the Oklahoma Historical Society, which put them on display in the State Capitol. However, a security guard stole the medals, and after they were recovered, the state decided they would be safer in the Oklahoma Historical Society. Through special arrangement with the Historical Society, Thorpe’s surviving sons William and Richard put the medals on display at the National Museum of the American Indian and at the London Olympics. Again, in spite of Jim Thorpe’s effortless grace as an athlete, nothing about his memory has been easy. There was another conflict about the resting place of his body. After his death in Oklahoma in 1953, his last wife Patricia removed his coffin and offered the towns of Mauch Chunk and East Mauch Chunk in eastern Pennsylvania the honor of maintaining his final resting place as a tourist attraction. The towns renamed themselves Jim Thorpe, PA, and now maintain a shrine and museum for him.

Thorpe’s children have lobbied for years for the return of his body to Sac and Fox territory. His surviving sons finally brought a lawsuit under the Native American Graves Protection and Repatriation Act. After the United States Supreme Court recently refused to hear an appeal by the Thorpe family, the case was over. Jim Thorpe, to this day, remains in the town named for him, Jim Thorpe, Pennsylvania.

In 1950, Thorpe was voted by Associated Press sportswriters as the greatest football player of the half-century. Just months later, he was honored as the best male athlete of the half-century. Three decades after Thorpe's death, the International Olympic Committee reversed its decision and issued duplicate medals to Jim Thorpe's children in 1983. Thorpe's achievements have been re-entered into Olympic record books, and he is now widely acknowledged as one of the greatest athletes of all time.

Jim Thorpe in 1912 wearing the mismatched shoes he found and wore in the Olympics after his were stolen.

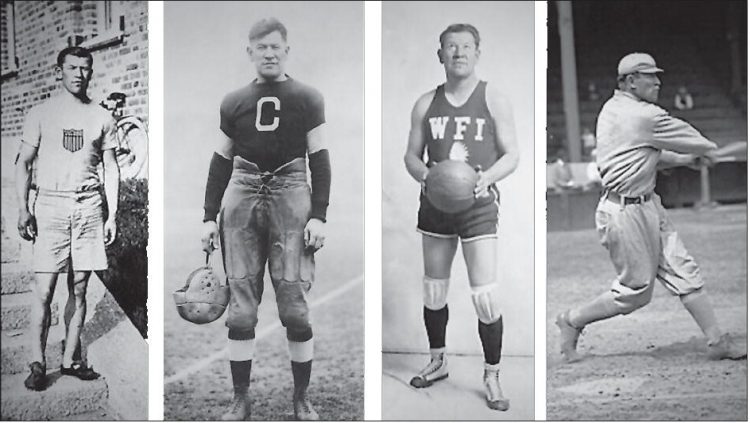

One of many statues of Jim Thorpe around his gravesite in Jim Thorpe, PA.