Searching for Eagles

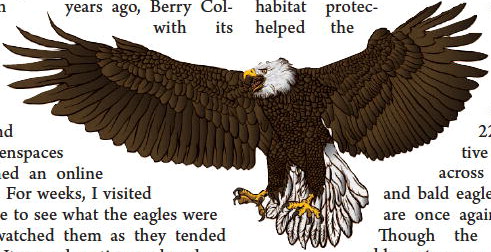

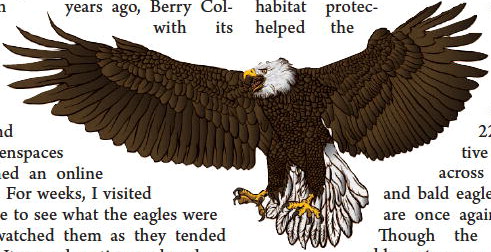

They’ve eluded me for years. As I hike or walk in the woods, I always scan the skies for a glimpse of a bald eagle, but I’ve never had the privilege of seeing one in the wild places of Georgia.

When my husband and I vacationed in Utah and Colorado several years ago, we stumbled upon some golden eagles eating a dead deer in a ditch beside an isolated highway. Until that moment, I didn’t realize eagles would feast on carrion, but they do, especially when live prey is scarce. I remember the enormity of those birds.

We returned to Georgia, and I continued to watch for a white head and a large yellowy-orange beak.

T h e n years ago, Berry College — with its magnificent mountain campus and rolling greenspaces — launched an online eagle cam. For weeks, I visited the website to see what the eagles were up to. I watched them as they tended their baby. It was exhausting work and represented both the labors of parenting and the miracles of nature.

“What are they doing?” my husband would ask sometimes when he’d catch me entranced by my computer screen.

“Look, the eagles are feeding the baby a fish!” I’d say.

Even their nest was an impressive feat — built in a tall tree with limbs strong enough to support several hundred pounds. Most are usually 4-6 feet in diameter, constructed of large sticks and lined with moss or grass. The bowl of the nest is usually about 3 feet deep — deeper than a kiddie pool.

Berry College is a mere 30 minutes away from my home, and every year, Facebook teases me with dozens of eagle photos snapped on the campus by everyday folks visiting for the day. Yet, I’ve visited the campus so many times, and I have never seen one of the beautiful raptors — symbols of our great nation.

Why is seeing an eagle in the wild so important to me? Well, they are beautiful, and I love birds, but there’s more to it than my interest in birding.

To spot a bald eagle in Georgia’s great outdoors — their striking white heads, neck and tail contrasting against the deep blue sky as they soar above the pines — is to witness a species that bounced back from the brink of extinction. There was a time not so long ago when America’s most iconic bird all but disappeared from the Peach State’s landscapes due to loss of habitat and widespread use of DDT. Throughout the 1970s, there was only one successful nest (a successful nest means that the parents fledged at least one eaglet) recorded in the boundaries of our state, and that one was on St. Catherine’s Island.

But in their darkest hour, hope spread its wings and took flight. In 1972, the U.S. government banned the use of DDT, and in 1973, they passed the Endangered Species Act, legislation that precipitated captivebreeding programs, reintroduction efforts, vigorouslawenforce- ment and habitat protec- tion that helped the species re bound. To d a y, there are 229 active nests across Georgia, and bald eagle numbers are once again soaring. Though the recognizable raptors are still on the state’s list of “threatened” species, their triumphant story demonstrates that when people work together, conservation miracles are possible.

Some people don’t care about vanishing species, but I do. When a species — any species — goes on the threatened or endangered list, it should be a wake up call to all of us.

Our wildlife is part of our heritage. It makes Georgia unique and a wonderful place to experience the outdoors. And because the effects of extinction are often felt throughout the food chain, losing even a single species can have disastrous impacts on the rest of an ecosystem (and that includes humans). Finally, the natural world is intensely interconnected. Our wildlife is an indicator of the health of our overall environment. When we tend to the environment and the wildlife around us, we tend to ourselves.

Thank God for eagles, and thank God their populations have bounced back. I hope to see an eagle one day soon, and I hope you do too. Until then, I’ll keep my eyes peeled as I search the open skies for these majestic creatures.