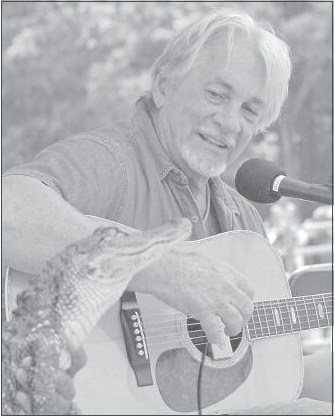

RIP Okefenokee Joe

We lost another great one last week. Dick Flood — also known as Okefenokee Joe — died on Monday, January 9, at the ripe old age of 90.

Those of us who grew up watching Georgia Public Broadcasting’s Swampwise and The Joy of Snakes (or remember Okefenokee Joe visiting our school) will miss his deep, smooth-as-butter voice and his songs and messages of respect for the natural world.

But did you know that before he became a beloved Georgia icon, he was Dick Flood, a gifted country music singer and songwriter who performed dozens of times on the stage of the Grand Ole Opry?

Having interviewed the beloved Okefenokee Joe a handful of times, I know his story well. He grew up in Pennsylvania, and as a young man, he spent his summers working as a counselor at a youth camp.

“I had fallen in love with country music, and so I taught myself how to play the guitar,” he told me. “After the campers were asleep, I passed the time by picking out songs and singing for the other counselors.”

He enlisted voluntarily into the US Army during the Korean War, and while stationed in the Philippines, he organized The Luzon Valley Boys, a country music band that played at military clubs on the island.

“After I got out of the Army and went home, I teamed up with an old Army buddy [Billy Graves], and we became known as The Country Lads,” he said.

CBS’s Jimmy Dean TV Show signed the duo as a regular act in 1956, which led to a recording contract with Columbia Records and two singles, “Alone in Love” and “I Won’t Beg Your Pardon.” When the show went off the air in 1958, Flood began concentrating more on his songwriting and found success.

Anita Bryant recorded his song, “Cold, Cold Winter.” George Hamilton IV recorded Flood’s “Gee,” which topped the charts in 1959. In 1962, The Wilburn Brothers recorded his “Trouble’s Back in Town,” voted by Cashbox and Billboard as the number one song of the year.

He had moved to Nashville and formed relationships with a veritable “Who’s Who” of the country music world — Bill Anderson, Eddy Arnold, Hank Snow, Minnie Pearl, June Carter, Jean Shepard, Jim Reeves, Ray Price, Loretta Lynn, Johnny Cash, and many others.

Then one Saturday night, Flood was invited to sing on the Grand Ole Opry.

“From 1959 to 1961, I had the honor of singing onstage at the Grand Ole Opry almost every Saturday night,” he said. “I filled in for the big acts. They paid union scale back then which was $11.75 per appearance, so I wasn’t getting rich doing it, but I loved it. Then one day, they didn’t need me anymore.”

Flood formed a three-piece group called The Pathfinders and began singing at military clubs across the globe. While on tour in Vietnam in 1966, Flood contracted Dengue Fever and almost died. His recovery was slow, and when he returned home, he couldn’t recapture the momentum of his early career. continued from page

Flood’s personal life was spiraling downward, as well. His second wife wanted out of their marriage. With two ex-wives and five children, he couldn’t make ends meet.

“My life was falling apart,” he shared. “I wanted to disappear, so I did.”

In 1973, he moved into a broken-down shack on Cowhouse Island in the Okefenokee Swamp and started the next chapter of his life. His friend paid him about $49 a week to take care of the exhibit animals — deer, black bears, alligators, raccoons, otters, bobcats, and other animals, and he began to understand his animal neighbors, befriend a few — even write songs about some of his experiences.

“That was one of the best times of my life,” he remembered. “I was free. I loved smelling the fresh air and hearing the sounds of nighttime. I loved learning and watching. I was living so close to the earth, and my mind was being opened. I was close to God.”

His wildlife lectures at the Okefenokee were instant hits.

“I didn’t feel like Dick Flood anymore,” he said. “So they asked, ‘What if we call you Okefenokee Joe?’ And I liked it. Okefenokee Joe had no past — just a future.”

After his sons moved to the swamp to live with him, he needed to earn more money.

“I got on the phone, called schools and other places, and booked Okefenokee Joe appearances on my off days to pull in more money, he recalled.”

He shared stories about the swamp, told a few jokes, played his guitar, and sang some of his nature songs. He carried a small army of snakes with him for demonstrations — holding the slithering specimens up while teaching students how to identify the snakes from far away.

“They were the ones doing the teaching, not me,” he laughed. Then he called Georgia Public Broadcasting (GPB) and pitched the idea of a nature show to them. After an interview, they produced three documentaries featuring the soft-spoken swamp teacher. People across Georgia fell in love with Okefenokee Joe and his earth-friendly philosophy. And so he took his show on the road for decades and shared his passion with millions — an unforgettable mix of soothing, inspirational folk songs, snake show-andtell, wisdom and wit.

During my last conversation with him, he said, “I’m too old to live in the Okefenokee now — too old to bend over and pick up a rattlesnake. Sometimes when I’m writing music about those days in the swamp, it makes me really sad. I miss it like an old friend.”

I remember hearing the pain and longing in his voice when he spoke of his beloved swampland.The world was a better place with Okefenokee Joe in it, and now we mourn. Rest in peace, dear friend.

From the PorchBy Amber Nagle

out of

Posted on