The Fire Still Burns

For his longtime advocacy of longleaf pine and prescribed burning on behalf of private forester landowners, Reese Thompson is the 2023 Landowner of the Year.

Forest Landowner Magazine

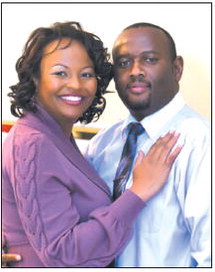

Reese Thompson does not fish, hunt, play golf, follow sports, or take vacations. He jokes that his profession, passion, hobby, and mistress are the same, and Pam Thompson, his wife of 37 years, gives her full blessing to his obsession with tree farming, especially longleaf pine.

Some forest landowners dabble in longleaf, the slow-growing, highermaintenance, wild hogattracting pine species that once covered much of the Southeast. Other landowners want no part of longleaf, which requires frequent burning, attracts endangered species, and does not produce timber as quickly as loblolly or other Southern yellow pine.

No matter, says Thompson, who, from his property near Vidalia, Georgia, has become one of the most visible longleaf advocates among forest landowners over the last two decades. For years, it seemed like he was one of the few landowners supporting longleaf. He’d attend longleaf-related meetings of state and federal officials, NGOs, and educational organizations, look around the rooms and realize not only was he the only landowner, but he was the sole person not paid to be there and on an expense report.

In the early part of his 20-year tenure as FLA CEO, Scott Jones would spot Thompson and marvel at both his commitment and the irony that the sixth-generation Georgian was among the only landowner voices in the room where others made policy impacting landowners.

“Reese would be the only one there other than FLA speaking on behalf of private forest landowners,” Jones said. “So many of these programs are aimed at assisting landowners without landowners in the room. You could count on Reese, spending his own money to be there.”

Thompson has worked tirelessly to show not only the value of longleaf but also that endangered species and forest management, including regular timber harvests, can coexist without loads of government regulation. For his ongoing efforts, he is the 2023 Forest Landowner of the Year.

“I am extremely honored and humbled to receive this recognition,” says Thompson, 69, who has endured long Covid in recent years. “I know I won’t be able to do this forever, but I’m a blessed man to have been able to do it for so long.”

Thompson grew up in McRae, Georgia, a town of 5,000 about 180 miles southeast of Atlanta, where his landowner family had been in the turpentine business for four generations, ceasing operations in 1981 due to a prolonged drought. Reese “worked tar” for two summers in high school, figuring there must be an easier way to make a living.

Reese graduated from the University of Georgia with a degree in finance and headed to the Chicago Board of Trade, the world’s largest commodity exchange. He worked for a grain company in Indiana for a couple of years, headed back to Chicago and experienced the highs and lows of trading and big-city life, before returning to rural southern Georgia.

Thompson’s father understood succession planning and how to avoid future disputes. A paved road split the property, and he gave one son the north side, the other the south, knowing they’d never be arguing about land lines.

Thompson ranks as one of his biggest accomplishments navigating the other side of succession when he purchased an adjoining property on three sides owned by one family for 140 years. It took 20 years and six attorneys to deal with three generations of heirs from New York to Arizona.

Thompson’s longleaf restoration work is part of a broader effort by the Longleaf Alliance and others to restore the Southeast’s native species and ecosystem. Besides the Thompson brothers’ properties in Wheeler County, the Alligator Creek Management Area (3,086 acres) is adjacent to older brother Frank’s land. In 2016, Georgia permanently protected Alligator Creek as part of the Gopher Tortoise Initiative, creating a large corridor of species like the tortoise and the Eastern indigo snake.

The Thompson property always had some longleaf, but Reese stepped it up a notch in the late 1980s when he discovered that containerized seedlings had a higher success rate than bare-root and could go into the ground yearround if there was moisture. “People would see me planting in July in 90-degree heat with 100 percent humidity and think I’d lost my mind,” he said. “But it gave me six months of additional growth.”

His focus on longleaf became an obsession in 2004 when he turned 50. He thought of his favorite tract, which has old longleaf and intact ground cover. His great-grandfather purchased it 130 years ago on the courthouse steps at a public auction for 14 cents per acre.

“I began wondering what my purpose in life was,” Thompson said. “I had no obvious talents and plenty of shortcomings. While showing the old woods to a wildlife biologist friend one day, she recognized the uniqueness. She identified twenty-nine plant species in a square yard. An intact longleaf ecosystem has been said to rival a tropical rainforest in ground biodiversity.”

He decided his mission was to protect, enhance, and restore the longleaf with which he had been entrusted. He became involved in longleaf advocacy, building close working relationships with FLA, the United States Fish and

continued from page

Wildlife Service, the Georgia Department of Natural Resources, The Longleaf Alliance, and the Orianne Society. He served 14 years on the Georgia Department of Natural Resources board, a term on the Longleaf Partnership Council, and six years on the USDA, Farm Service Agency, Georgia State Committee. He’s a past chairman of The Longleaf A lliance, and spent six years on the Partners for Conservation board.

“Planting longleaf is the closest to immor tality that I will achieve,” he says. “I would rather be remembered by family and friends as a good steward of the land than CDs in a bank.”

Thompson admits that not everyone can afford to go all-in on longleaf and approach forest ownership as much as advocacy and labor of love as they do business. His good friend and fellow longleaf advocate Bill Owen, who nominated him for the award, has transformed his 1,850 family acres in Virginia to longleaf, though Owen has no heirs and is retired from an unrelated career. Thompson, who says he owns or manages “ several thousand” acres in Georgia, refers to his wife Pam as his “backup foundation,” having started two successf ul businesses. “I’m one of her employees,” Thompson says. “ She enables me to do what I enjoy doing.”

That means Thompson can devote his full attention to longleaf, which due to his efforts and those of others, has shifted the perception of longleaf for many forest landowners over the last decade from a no-way-never proposition to an attractive possibility.

That’s because state and federal grants, including one offered via the Forest Landowners A ssociation, provide landowners the funding to plant, burn, and manage longleaf. Because landowners have no recourse if a disaster destroys their forests, at least until Congress passes the Disaster Reforestation Act, longleaf looks attractive because of its more fire and storm-resistant characteristics. The market for longleaf pine straw can command up to $300 an acre, and longleaf provides valuable wildlife habitat.

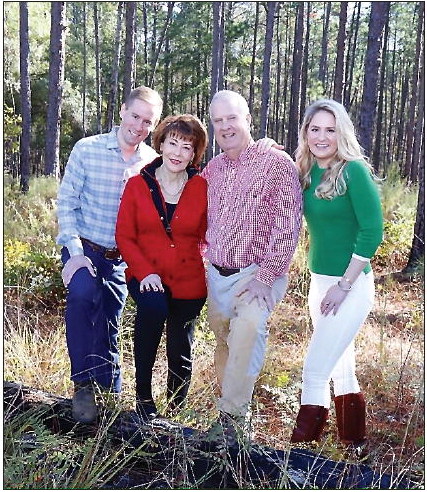

Then there’s the fun you can have playing with fire. Since longleaf requires frequent burning, landowners find it costeffective, more rewarding, and most enjoyable to do it themselves. When the Thompsons’ children, son Reese II and daughter Audrey, were at the University of Georgia, they ’d bring their suburban-raised friends to their property in W heeler County, about 180 miles southeast of Atlanta. The older Reese would give the wide-eyed newcomers drip torches and tell them to “walk that way and create fire until I tell you to stop.”

Thompson is such a fire enthusiast that he believes we should rethink the traditional climate of heaven and hell. “My idea of heaven is a cool winter day, and I’m burning wiregrass and longleaf,” he says. “I like to think of myself as an artist who creates landscapes with fire.” Like the friends of Thompson’s children, who were taught to avoid fire, most people think of forest fire mostly as the annual infernos that rage out west, partly because of poor public forest management. Since1947,A mericans have listened to Smokey Bear stress that “only YOU can prevent forest fires.” The well-intentioned campaign aimed at getting people to douse campfires and stop tossing cigarettes from cars instead created the public perception that any forest burning was terrible.

“Everyone has v isions of Bambi being burned, butnotal lfirei sbad,” Thompson said. “Fire i s nature’s way of cleansing and recycling the forest, which will happen sooner or later. Under good conditions, you can make a fire do what you want.”

Thompson was pondering how to change the perception of fire one day while riding in his Whitfield planter, which he uses to plant 605 longleaf seedlings an acre. He hit a stump, struck his head on the vehicle’s roof, and was inspired to create Burner Bob, the prescribed fire advocate’s answer to Smokey Bear.

continued from page

Unlike a bear, a bobwhite quail is a warm, fuzzy creature that responds well to fire. Thompson traveled to Atlanta to the offices of the International Mascot Corporation, which has produced thousands of iconic fuzzy costumes for sports teams and companies. The result was the smiling, 8-foot, Burner Bob, a “cool dude with a hot message” that the forests need fire to survive. Burner Bob shows how to burn safely. (Burner Bob is a registered trademark and the “cool dude with a hot message” a registered slogan.)

The Burner Bob character accompanies Thompson and others to conservation events and fire festivals. The mascot is especially popular at school presentations. There are educational Burner Bob videos, cartoons, coloring books, and other materials geared to “spread the flame.” Though Thompson spent considerable funds on the mascot costume and collaterals, he licensed it for $1 to The Longleaf Alliance and makes no money off Bob.

“Bob helps educate children that not all fire is bad and that it needs to be conducted by experienced people in favorable conditions when permitted,” Thompson says. “You have to start with the children to start turning the ship of perception around, but it’s a long process.”

Thompson has conducted a similar public relations campaign for the indigo snake, though without the fuzzy costume, and geared more toward addressing the inconsistencies in endangered species listings. The muscular, blue-black, non-venomous snake, the longest native North American species at eight-plus feet, eats rattlesnakes and cottonmouths. The U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service listed the indigo snake as a threatened species in 1978.

Thompson notes that despite the indigo snake listing, there’s never been logging restrictions, unlike the policy surrounding the black pine snake. He’s addressed it with the USFWS.

“I’d never meet anyone from Fish and Wildlife until 15 years ago; I thought of them as cousins of the IRS,” Thompson said. “Now I have a lot of good friends there. But I told them, ‘You dropped the ball on the black pine snake.’ We’re blessed with indigo snakes, log around them, and nobody has ever said, ‘You can’t do this’ because you have indigo snakes, even though it’s been federally listed since 1978. It’s a double standard, and I don’t know what Fish and Wildlife’s motive was with the black pine snake.”

As head of FLA, Jones notes that such government bureaucracy and inconsistent application of endangered species policy is why many landowners understandably shy away from talking about endangered species on their land. Thompson, meanwhile, creates public relations campaigns about threatened species such as indigo snakes, gopher tortoises, and spotted turtles co-existing within best-practices forest management.

“Reese has not been afraid to talk about what’s on his property,” Jones says. “He doesn’t manage in fear of what might happen. He’s proactive when he says, ‘I think we can manage with these things and make them a value-add to the property.’ He can strike a balance between having regulated species and not having adverse relationships with regulators.”

Owen, the Virginia longleaf grower, calls Thompson a “practical conservationist” who walks the line between ecosystem and forest business. “Reese is committed to the mission of protecting, enhancing, and restoring the longleaf ecosystem entrusted to him while maintaining a solid investment in forestry and forest products for the future,” Owen says.

Jones says he can envision a time when the government and private businesses will provide credits to landowners for managing for endangered species, not unlike mitigation or carbon credits. “Land might become more valuable the more those species use it,” Jones said. “Reese could prove to be ahead of his time.”

Thompson says he wants to improve that future in other ways. He enjoys planting bald cypress in wet areas, knowing that someone will stumble upon them 50 years from now and know that someone planted it.

“Owning land is a discipline that keeps me grounded,” he says. “Continuing to add to the footprint keeps me working and prevents me from being tempted by detrimental activities. My mission is to protect, restore, and enhance what has been entrusted to me while serving as a good role model for the next generation.”

Pete Williams is the editor of Forest Landowner magazine, official publication of the Forest Landowners Association. For membership information, please visit forestlandowners.com.

THE FIRE MUST BURN – Regular prescribed burning is a must for longleaf management.

SUPPORTING PRESCRIBED BURNINGS – Reese Thompson (right) and son Reese Thompson II (left) appear at an event with Burner Bob, the mascot for prescribed forest burnings.

LANDOWNER OF THE YEAR – Reese Thompson has earned the Landowner of the Year award for his work with advocacy and management of forest property.

ADVOCATE FOR BURNING – Thompson has introduced many to the joys of prescribed burning.

PROFITABLE INVESTMENT – Well-managed longleaf pines like Thompson’s can becomea lucrative pine straw operation.