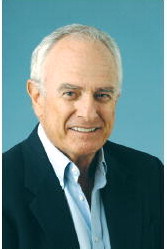

Loran - Smith

Loran

Jeff Treadway, second baseman for the Atlanta Braves during the worst-tofirst era of the nineties, was a small-town boy who could only dream about spending time in the Big Leagues during his formative years. His name was not on anybody’s “must” prospect list. If there were tryout camps within easy traveling distance, he was not favored a priority invitation. He could only “walk on.”

In fact, he was not highly sought after by Southeastern Conference teams when he was finishing at Middle Georgia College in the spring of 1980, but a funny thing happened on his way to Gainesville, Florida, where the Gators were keen on his signing a baseball grant-in-aid.

Steve Webber, the late Bulldog baseball coach who had recently taken over in Athens, aspired for Treadway to join him and the Bulldogs. At the time, Treadway was sold on wearing orange and blue, because of Florida’s elite status as an SEC powerhouse, although he had always been a UGA aficionado.

Webber asked Vince Dooley, football coach and athletic director, to reach out to Treadway, which led to a life changing vignette in the young infielder’s life. Jeff was staining a downstairs deck at home one day when his mother told him he had a phone call which he tried to deflect. “I can’t come to the phone now, I have stain all over me, I’m dirty and too messy,” he responded.

With that his mom said, “Well, I will tell Vince Dooley you can’t take his call.” That missive resounded like a lightning bolt. Jeff almost put himself on the disabled list, crashing into furniture, as he sprinted up the steps to engage in conversation with the Georgia boss.

When Jeff eventually got to Gainesville, Fla., he was wearing the Red and Black of the University of Georgia and now considers a conversation with Dooley a turning point in his life. He can’t get enough of Athens and Georgia. “I go there as often as I can,” he says. “It is the greatest place on earth.”

With utility being an asset—he played 3rd base and 2nd base and some shortstop—it was Jeff’s left-handed batting stroke that got him to the major leagues and kept him there for nine seasons. With the Braves, he played on two World Series teams and experienced a career highlight against the Phillies in Philadelphia on Mike Schmidt’s jersey retirement night.

It should have been “Jeff Treadway Night.” Jeff hit three homeruns and came within a foot or so of a fourth. “I was always a fan of Mike’s and never expected such an exciting game to happen for me,” Treadway says. While hitting from the port side in a league of abundant righthanded pitchers, Jeff hit two homers out of the park against left handers and can tell you the pitches he hit in his unforgettable outing.

“The first one was off one of the top starting pitchers in the league at the time, Pat Combs. I hit a 95-mph fastball to right center. The next lefty came with a breaking ball down and in. I caught it just right and there was no question, it was continued from page

going deep in the right field seats. The third homer was off a right hander named Acer Feld. He was behind in the count and came with a high fast ball and that was the pitch I was looking for and connected with it.”

When he reflects on his career, he always expresses gratitude that he not only made it to the Big Leagues, but that he had a memorable four years in Atlanta. Growing up in Griffin, about 45 miles due south of Turner Field, he remembers watching weekend Braves’ games with his father, Wes, dreaming that he might be fortunate to play for his favorite baseball team but not expecting it to come about.

While he did not become a rich man playing the game he loves, Treadway did reach the annual salary threshold of $1 million dollars plus and put his good fortune in this perspective. “My dad likely did not earn a million dollars in his lifetime.” Jeff will always be grateful for what baseball did for him, emotionally and financially. Humility and ambition have always been his “most valuable” emotional companions.

While he is not sure of his status as the master of the hidden ball trick, Jeff may be one of the last big leaguers to pull off the trick successfully. In the minor leagues, a coach Jeff Cox showed him how to place the ball outside the top of his glove and cover the ball with two fingers. When he turned his glove over you couldn’t see the ball.

In a game in San Diego, a batter successfully bunted a runner to second base, Jeff covering first and getting the putout. He pretended to give the ball to Steve Avery, the pitcher, and told him to stay off the mound. He then whispered to the umpire that he had the ball.

When the runner stepped off 2nd base to take his lead, Jeff tagged him out. The Padres didn’t know what happened, Braves manager Bobby Cox didn’t know, the announcers didn’t know, and the fans certainly had no clue. However, they booed Jeff unmercifully once they found out what happened for the rest of the evening. “They never let up,” he laughs and the tough thing for me, it was a doubleheader, so they had plenty of opportunity to try to make me miserable.”

The hidden ball trick is legal if you can pull it off, and Jeff suspects one of these days somebody will find the opportune time to catch a team napping.

Jeff helped his team win an important game, but he didn’t gain the notoriety of a minor league catcher named Dave Bresnahan of the Williamsport Bills.

In a game with the Reading Phillies on Aug. 31, 1987, he hid a peeled potato in his pants pocket. With a Phillies runner on third taking a big lead, Bresnahan threw the potato to third, causing the runner to sprint for home whereupon Bresnahan tagged him out.

The umpire called the runner safe which caused the club to release Bresnahan the next day for his unsportsmanlike act. But the fans loved it. They made such a fuss about Bresnahan’s sleight of hand that the club eventually retired his number.

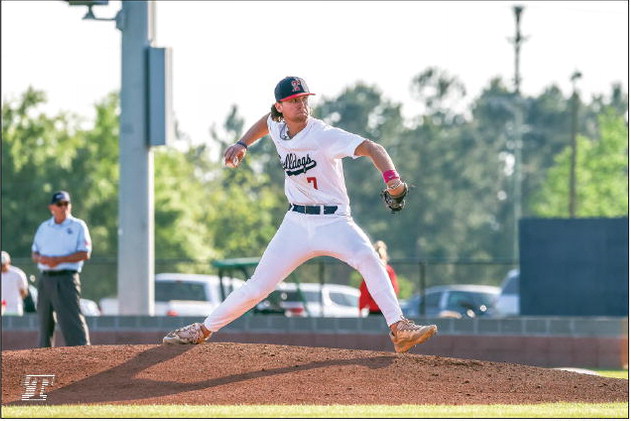

Following retirement from baseball, Treadway managed briefly in the Braves minor league system and then coached baseball at Stratford Academy in Macon for 20 years. He plays in charity golf outings, follows Bulldog sports teams, and keeps his homestead tidy and neat. It’s a good life for a Damn Good Dawg who could hide the ball with the best of them. You could also say he was a pretty fair country hitter.