It’s a Family Tradition - Powell and Horne Families Making Syrup for Four Generations

It’s a Family Tradition

Every year on the weekend before Thanksgiving, a Wheeler County family gathers to continue a tradition now in its fourth generation. Sugar cane is harvested and ground, the juice is filtered and poured into a 100-gallon cast iron kettle, and the process of syrup making gets underway.

It all began with B.L. Powell in Treutlen County in the early years of the 20th century as the hardworking farmer harvested sugar cane and boiled it down to make syrup. His annual syrup making was not just for producing a commodity people needed and wanted, it was an opportunity to hold gatherings for family and friends.

Years ago, syrup boils were commonplace in the South. Families depended on the syrup as a sweetener because sugar was expensive and scarce. Almost every farm boy learned about the process from his elders, and it was just expected that the tradition would be carried on. But syrup making is time-consuming, intensive, and exact, from cultivating and harvesting the cane, to stripping the leaves from the stalks and grinding the cane to extract the juice, to spending five to six hours over a steaming cauldron to produce the syrup. It takes skill to keep the cooking temperature high enough to boil but low enough not to scorch (228 degrees), and constant skimming to remove impurities as the syrup cooks.

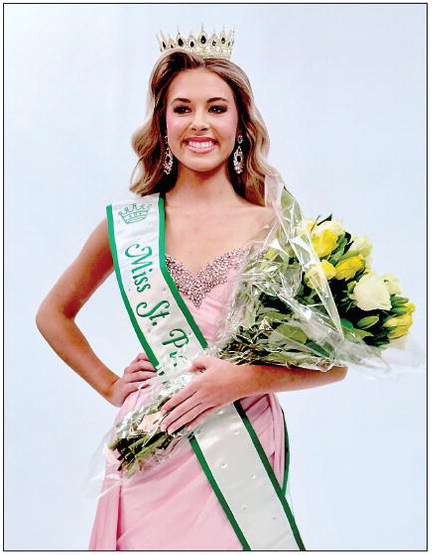

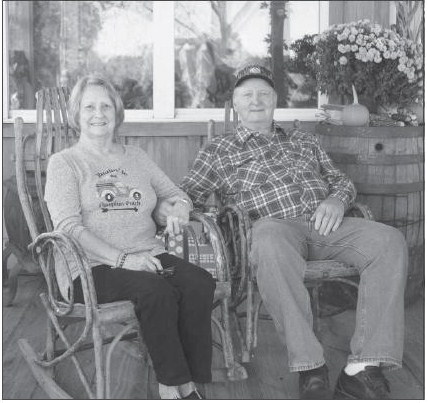

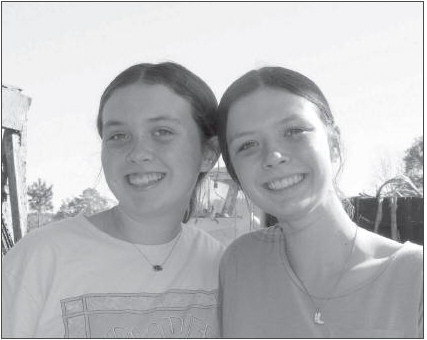

Now, only the heartiest of souls have continued the tradition to ensure the art of sugar cane syrup making is not lost to the ages, and, as in the case of the Powell descendants, because the process also brings together family and community. The Powell and Horne Families B.L. Horne, named for his maternal grandfather B.L. Powell, is now at the helm of his family’s annual syrup making, but he has an army of kin and friends supporting him in his endeavors. B.L.‘s home is located about six miles north of Glenwood on Georgia Highway 19. His wife, Ginger, is an educator who just this year assumed the position of middle school principal at Wheeler County School in Alamo. The Hornes have two daughters, Alayna, 13, and Lydia, 16. B.L.’s parents Louella Powell Horne and Colen Horne, Sr. live close by.

When Louella and Colen married, B.L. Powell enlisted the help of his son-in-law in work on his Treutlen County farm, and that included cultivating sugar cane and syrup making. “You talk about doing some work, I have done it in the past,” Colen said of helping his father-in-law on the farm. Syrup making time was fondly anticipated but also dreaded. “He’d work the fool out of us stripping, topping, cutting down, and loading the cane and carrying it to the mill. For two months I’d go over every day getting ready to make syrup.” There was also the fall hog butchering on top of everything else that had to be done.

But the hard work always paid off. In those days, families were selfsufficient. Colen not only formed a strong work ethic, but gained useful skills he could pass along to his children and grandchildren who still practice what he taught them.

Louella said her father, who passed away in 2012, lived in Treutlen for the rest of his life after marrying Jimmie Hardy. The Hardy family had a long history in the county; Jimmie’s father was farmer Charles Mack Hardy. Louella recalls how her father set aside mayonnaise jars all year for syrup bottling. The recycled jars might have saved some money, but preparing the jars for bottling syrup was an arduous task. “We had to soak the jars to remove the labels, scrape off the labels, then scald and sanitize the jars,” Colen shared. He lamented that the price of bottles and corn syrup used to stabilize the cane syrup have risen to the point that cane syrup is not only unprofitable, it is downright costly. “Bottles have gone from $7.90 a case to $10 a case. Corn syrup had gone from $38 for a five-gallon bucket to over $50 a bucket.”

Colen reflected that he has been involved in syrup pretty much since he was discharged from military service and married Louella. Even though he was taken under B.L. Powell’s wing, so to speak, and taught all about farming, he didn’t end up making a career of farming himself. He worked for the prison system and ended up planting pine trees. Now, like his wife, a former teacher, Colen is retired and enjoys supervising the syrup making at his son’s farm. “A couple of years ago, I turned it all over to him and I just come to enjoy it,” he said.

“He has modernized what we used to do and made it easier,” Colen said of how his son has streamlined the syrup making process.

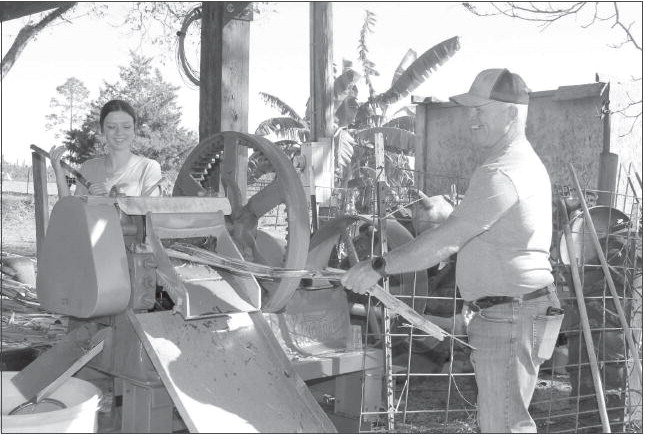

In the old days, B.L. Powell used a mule to pull the grinder. “We use a Deere — a John Deere tractor,” B.L. Horne quipped. A tractor-driven grinder makes squeezing the juice from the cane easier, faster and more efficient. The juice is crushed between rollers, collected in a vat at the bottom of the grinder, pumped into a 100-gallon overhead holding tank, and funneled to the kettle for cooking. The process is much less labor intensive than in the old days when the juice was collected in Number 3 wash tubs, cov- continued from page

ered with burlap to keep out flies and debris, and hauled to the kettle by manpower.

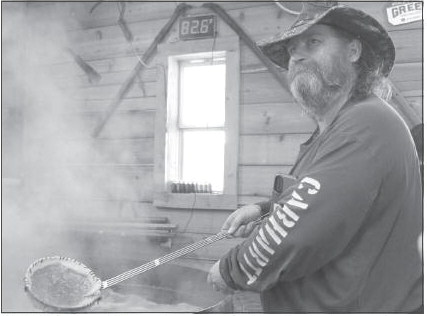

“It is filtered four times before it goes to the kettle,” B.L. explained of his modernized process. The juice is cooked for five and a half to six hours, with the kettle coming to a frothy boil and impurities being skimmed from the top with longhandled ladles fitted with porous cloth. Another part of the process is the continuous wiping of the rim of the kettle to keep it clear of syrup that has boiled over, and to do so without burning your hand. In the old days, children loved to eat the “syrup candy” that formed on the rim.

Even with modernization, syrup making is still hard work. There are no short cuts for the cultivation and preparation of the cane. B.L. welcomes the help he gets each year from family and friends.

B.L.’s daughter Lydia, a tenth grade student at Vidalia Heritage Academy, said she likes to work alongside her father in the fields and in the syrup house. She seemed at ease in the cane fields where she described how the cane left standing in the field will be used to seed next year’s crop. She talked about the characteristics of the various types of cane the family has cultivated. “We have used Big Red, a chewing cane that produces a lot of juice; and we’ve tried Yellow Gal, that’s a greenish yellow color. Now we use Improved POJ,” she said of the cane favored by her grandfather, Colen, which he said has the best taste and strips more easily from the stalk.

Lydia, who hopes to become a large animal veterinarian, said she plans to continue the family syrup- making tradition. Her younger sister, Alayna, echoes her sister’s sentiments about the family tradition. She especially enjoys the people who come to the annual syrup boiling and reminisce about their own family traditions.

B.L. and his father built the structure they now use for the syrup boiling. They have a saw mill and cut the various types of hardwood used in the construction of the syrup house. The family also has a tractorpowered grist mill and they make grits and cornmeal that are sold alongside barbecue sauce, jellies — and, of course, syrup — at the syrup house.

B.L. is not only a farmer and master syrup maker, he is a pastor and city administrator in Mount Vernon. He just preached his last sermon at South Thompson Baptist Church where he served for 13 years and is stepping into a new position at Southside Baptist in McRae.

He also smoked the pork that was made into pulled pork sandwiches and sold to hungry crowds at the syrup making. Surrounded by happy chatter and the lilting strains of gospel and bluegrass music inside the syrup house, B.L. was focused on the task at hand but still stopped to converse with guests. “We do this for the fellowship,” he said.

As his brother Chris worked alongside him skimming the steaming kettle which would cook down to about 10 gallons of syrup, B.L. had been on the job since early that morning and was looking at finishing the boil around 9 p.m. His grandfather was known for accomplishing 20 cookings during Thanksgiving week. By the time the day ended, B.L. and his family would have cooked 800 gallons and capped 1100 bottles of syrup. The History of Sugar Cane and Syrup-Making Sugar cane is an ancient crop that came to the New World with the Southern Europeans. The plant adapted to the semitropical regions of the southern United States, and during its heyday had an impressive impact on the economy.

In the early 1920s, sugar cane syrup production reached 41 million gallons— indicating that Americans were consuming about one gallon a piece per year of the syrup. Sugar cane syrup production in the 1920s was about equal to the production of sweet sorghum (a close cousin of sugar cane). By 1950, sugar cane production had waned, and was considered more of a small farm enterprise.

Table syrup can be made from sugar cane or sorghum, both members of the Gramineae (grass) family. Traditionally, sorghum is grown further north. While sugar cane and sorghum are closely related, they are distinctly different, right down to the taste.

The type of sugar cane used to make syrup most definitely affects its taste. Sugar cane comes in several varieties, ranging from white to purple, grey and pink, to yellow-green or green, and can be tinged with colors ranging from brown to claret, with names like Bourbon, Elephant, Caledonian Queen, Keni Keni, and many more. The origins of sugar cane can be traced to multiple regions of the world, and some historians estimate the crop may have been cultivated as early as 8000 B.C. It spread along the trade routes from Africa, Asia and China to the New World. Now, there is a renewed interest in sugar cane production — and the machinery involved in the process — but only as a legacy. “We don’t do this to make money. There is no profit except fellowship and keeping a tradition alive,” B.L. Horne avowed.

Like the Hornes, many families and entire communities celebrate fall each year with sugar cane grinding and syrup making. There are even organizations that are dedicated to perpetuating the art of syrup making as a facet of American history that must be preserved.

READY TO ROLL—Stripped sugar cane stalks lie on a wagon waiting to be rolled through the grinder. The cane the Horne family favors is a variety called Improved POJ, but they have tried numerous others.

AMBIENCE — An old buggy decorated with fall finery sits outside the syrup shed.

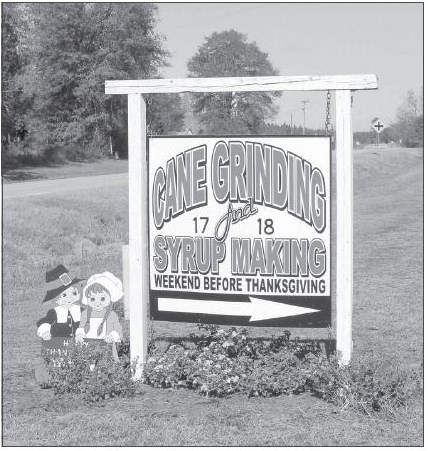

THIS WAY, PLEASE — A colorful sign positioned on Georgia Highway 19 about three miles north of Glenwood in Wheeler County invites guests to join the fun at the Horne family syrup house.

GRINDING CANE — “Adopted uncle” Billy Knight is among the family and friends who gather to help the Horne family during syrup making. Here, he assists Lydia Horne as she feeds cane into a tractor-powered grinder.

JUST ENJOYING THE EVENT — Louella Powell Horne, left, and Colen Horne greet guests front the front porch of the syrup house. Louella’s father, B.L. Powell of Treutlen County, established the family tradition of Thanksgiving Week syrup making. Colen took over the syrup-making tradition from his father-in-law.

A LITTLE MUSIC—The Kramers from Lyons entertain guests with some toe-tapping gospel and bluegrass tunes. They are regulars at the Horne family syrup makings, which have been held at B.L. Horne’s farm since 2019.

HOW ABOUT A BOTTLE OF SYRUP? — Ginger Horne holds up a bottle of the Horne family sugar cane syrup. Guests at the syrup making can purchase syrup, jams and jellies, barbecue sauce, and freshly-ground cornmeal and grits made by the Horne family.

SKIMMING — Chris Horne, B.L.’s brother, is enveloped in steam from the kettle as he works to skim impurities from the surface of the boiling syrup. This is a task that demands constant supervision. The fewer the impurities there are, the clearer and tastier the syrup will be.

IN THE FIELD — Lydia Horne stands in a field of sugar cane that will be used to seed next year’s crop. The family grows about one acre of sugar cane on the family farm, but also acquires cane from other sources.

SISTERS — Alayna Horne, 13, left, and Lydia Horne, 16, look forward to syrup making each year. Both plan to keep up the family tradition.

POPULAR SPOT — Rhonda Herndon Horne of Treutlen County, sells pulled pork sandwiches and homemade pound cake at a table on the porch of the syrup house. Her late husband Colen Horne, Jr., was the business man behind family operation.