The new Arab street is here at home

The old conventional wisdom was that the U.S. couldn’t be too pro-Israel for fear of inflaming “the Arab street.”

The new conventional wisdom will have to be that we can’t be too pro-Israel for fear of inflaming “the Western street.”

The Arab street, a hoary cliche of commentary on the Middle East for decades, was a reference to public opinion in the Arab countries, with the strong implication that if we offended it, the result would be massive anti-Western demonstrations and perhaps violence.

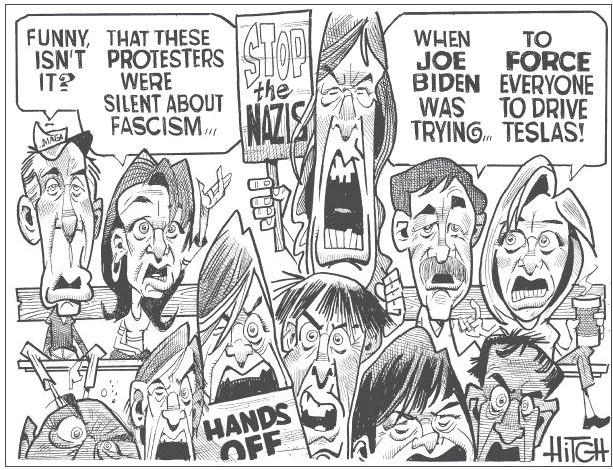

Well, here we are, with this dynamic playing out throughout the United States and other Western countries. We have offended the new Arab street within our own societies. In response, it has lashed out in mass protests, intimidation of Jews, antisemitic chants and graffiti, property damage and anti-patriotic acts and sentiments.

It is hardly the global intifada that speakers at these events call for, but it is significant agitation. Left-of-center political parties will take it seriously, and the Biden administration — hesitant to speak of antisemitism without reference to fashionable Islamophobia, as well — has already been influenced by it.

The Arab street in the West is not literally Arab, although Muslim immigrants and their children, along with foreign students, are clearly a large component. Woke young people who come by their anti-Israel views via intersectional politics, along with traditional left-wing and anti-war activists, play a big role, too. It makes for a noxious mix. The West’s Arab street mobilized in the immediate aftermath of October 7 before Israel even had the chance to mount any substantial response. It inveighed against Israel on principle even after an unspeakable pogrom.

Of course, things have only picked up from there. A week or so ago, more than 300,000 pro-Palestinian protesters marched in London, chanting for the elimination of Israel. That would be a notable crowd in an Arab capital, but it’s especially remarkable in one of the greatest cities in the Western world.

In a nice touch that, again, one would expect in a country in the Middle East, the protest march ended at the U.S. Embassy.

A couple of days earlier, thousands of protesters shut down midtown Manhattan. They vandalized a police cruiser, writing “IDF KKK” on it, and splattered fake blood on the New York Times building. They kicked and smashed windows at a shut-down Grand Central Station.

Unlike other mass movements, most famously the civil-rights movement, the protesters don’t seek to swath themselves in American symbolism and ideals. Palestinian flags, not American flags, are the banners of these marchers. In Manhattan, they removed American flags from a lamppost. And they’ve vandalized war memorials in Europe.

In some prominent cases, we have directly imported hatred of ourselves via the Middle East. At a large pro-Palestinian rally in Washington, D.C., the lawyer and activist Lamis Deek praised martyrdom and resistance, and bellowed that “the truth is the Western world is a lie.” She comes from Nablus, and her worldview is about what you’d expect of someone from there.

At MIT, Israeli and Jewish students say they were blocked from attending class by a pro-Palestinian protest at the school’s main entrance. The protest violated the rules, but when the school ordered all protesters to leave the area or face suspension, the contingent of Jewish counter-protesters left, while the pro-Palestinians stayed.

Were they suspended? No, apparently because many of them are foreign students. The president of MIT cited “visa issues” in not following through on the discipline.

This is perverse. But we can never forget the extent to which we ourselves, through determined inculcation in our own schools, have made students from right here in the United States haters of Israel and the West. Altogether, we’ve created the conditions for the ongoing cataract of anti-Israel agitation, coupled with outright antisemitism and harassment of Jews, that shows no signs of abating.

Why settle for an Arab Street abroad, when you can have one here at home?

Rich Lowry is editor of the National Review.

(c) 2023 by King Features Synd., Inc.