editorials

Another Monteen

Georgia Magazine asked me to write a story about people who rescue and rehabilitate birds of prey, and after a Google search, I found Hawk Talk, a wildlife rehabilitation center 40 minutes from my house. My husband and I drove over and met Monteen McCord and the hawks, owls, and other raptors in her care.

After the usual introductions and pleasantries, I told her of another Monteen.

“I had an aunt named Monteen,” I blurted out. “She was born in 1925 and raised in Toombs and Tattnall counties. It’s such an unusual name, and I have never met another one until today.”

Monteen McCord shared that her mother loved the name and believed it was of French origin.

But Monteen is far, far from French. She’s pure Southern. She uses the same expressions and phrases I have heard for my entire life and taught me a few I didn’t know.

One by one, I lobbed my interview questions at her.

“Can you tell me about one of the times you returned a hawk or owl back to nature?” I asked.

She was direct with me. “I wish I could tell you that all releases have happy endings, but that would be a damn lie,” she said. “Things go wrong sometimes. The birds don’t always survive. It hurts.” She got a faraway look in her eye and continued.

“Thirty years ago, I rehabilitated a female Red-tailed hawk. She’d been shot, and it took a while for her to heal. I couldn’t return her to her old territory, so I released her near my home. We lived in a wooded area with a 50acre pasture in the front lined with woods.”

Monteen released the great bird and watched her take flight, her large wings flapping and giving her lift into the wild blue yonder.

“But then I saw something out of the corner of my eye,” she said. “Another hawk launched from a nearby tree and made a beeline for her. It was a moment of terror. I braced for the worst.” The two hawks circled one another. “After a couple of minutes, I realized it was a male hawk,” she said, tears welling in her eyes. “They did the circle dance a few more times then flew off together, and I cried like a fat dog.” She’s saved hundreds of birds of prey. She told me about nursing owlets to maturity and explained how to train hawks to hunt by using a hacking board. A few times she got sidetracked and told me about the time she stole her mother’s cremation urn and ashes from her sister’s house and how her ex-husband, who was a “neat freak,” married a woman who has obsessive compulsive disor- continued from page

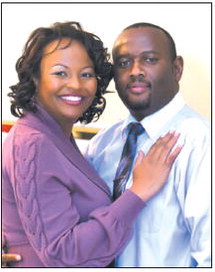

der (OCD). “For them, a good time is a Friday night spent cleaning the house from top to bottom,” she said with a laugh. At Hawk Talk, Monteen’s a one-woman show. She cares for the birds of prey, but she also hits up people for money, a necessary part of her job she doesn’t enjoy. “We always need more mouse money,” she told me. “A live mouse costs about $.83, and some birds eat one a day and others eat six or seven, so you do the math…” We ventured to the shelters where the birds of prey live. I was instantly hypnotized by the owls’ big glowing eyes. Monteen gave me a leather glove and showed me how to hold a raptor — “like you are holding a beer,” she said. Then she perched a gentle barred owl named Fiona on my glove, and just like that, I was holding an owl. We walked down to another shelter and she fetched Cotton, a colossal great horned owl. “Those tufts on his head are feathers, not ears,” she said. “His ears are back here.”

She lifted the small feathers on the side of his head exposing tiny openings.

“The shape of his face helps funnel sound to his ears. Owls have extraordinary hearing,” she said. “And their eyesight is incredible, too.” Then Monteen began to transfer colossal Cotton to my glove, but Cotton didn’t like me. Cotton rebelled. Cotton’s talons were as big as my hand and his claws looked as sharp as razor blades. After a bit of a kerfuffle, Monteen regained control of Cotton and said, “Well, maybe you should just pet his back.”

And so I did. The visit to Monteen’s sanctuary was educational and helped me understand the heart of wildlife rehabilitators.

“It’s like the little kid tossing stranded starfish back into the ocean one at a time,” Monteen said. “Wildlife rehabilitators don’t affect the population dynamics as a whole — we just help one injured or orphaned animal at a time.” Monteen McCord says through her work saving birds of prey, she hopes to earn enough spiritual brownie points to get through the pearly gates.

She need not worry. Just like the other Monteen I knew, she’s earned her wings.

From the PorchBy Amber Nagle

Amber holding Little Fiona.