Hello Traveler

It was cold out there in that field, as the sun slipped away beyond the horizon. My husband and I, with our golden retriever wedged between us on the console, sat in the warmth of the truck looking out the front windshield toward the west.

“There’s Venus,” I said, scanning the deep blue just above and to the right of the bright planet. “But I don’t see the comet.”

“It may be too early,” Gene said. We sat, we watched, and we waited for comet Tsuchinshan-ATLAS to make a grand appearance in the October sky last week. Around 7:50 p.m., Gene took a photo with his phone, setting the exposure for seconds longer than a daytime photo. We looked at the screen.

“There it is!” I said, as I pointed to a faint tail.

And then we both got excited, because the two of us are unashamed science nerds.

“Hello traveler!” I said. Let me explain. Tsuchinshan-ATLAS is a long-period comet that orbits the sun every 80,000 years. It has only been visible to us earthbound humans for a very few days, and when it’s gone, no one living in this world will see it again. Our children won’t see it. Our grandchildren won’t see it. No one will see it again for another 80,000 years as it hurls through space. It is like laying our eyes on a rare and precious gem — a marvel.

Comets are celestial wanderers with long, gossamer tails that stretch across the dark sky. At their core, comets are composed of a mixture of ice, dust, and rocky material — remnants from the formation of the solar system. Often described as “dirty snowballs,” they are frozen chunks of ancient cosmic debris. When a comet’s orbit brings it close to the sun, the heat causes its icy nucleus to turn from a solid to a gas — creating a glowing halo around the ball known as a coma. Solar winds then sweep dust and gas away from the comet’s core to form the tail that points away from the sun.

These travelers follow elliptical paths that carry them on long and lonely journeys through the solar system. Their orbits are often elongated, taking them from the frigid outer realms near the Kuiper Belt or the far more distant Oort Cloud, into the warm inner solar system where we earthlings reside.

Comets can appear as periodic guests in our skies, such as the famous Halley’s Comet which returns every 76 years, or they might be newcomers, sent on a once-in-a-lifetime passage by a gravitational nudge from a planet or another celestial body.

As for Gene and me, once we knew where in the dimming sky to direct our gaze, we could capture it with our binoculars and our iPhones. Indeed, we took several photos trying to get the perfect shot to share with family and friends. We texted our images with pride. I posted our photos on Facebook. continued from page

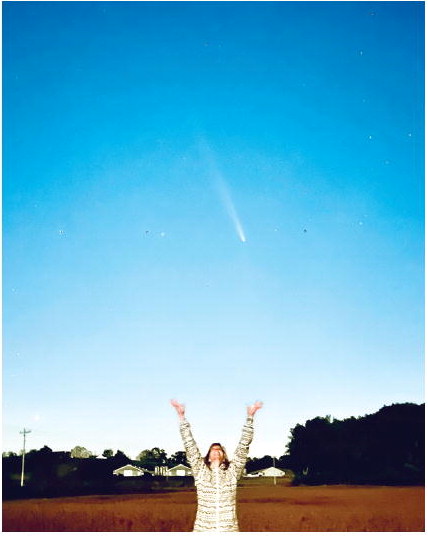

The following day, we drove to another field with an open view of the western sky to see it again, though its visibility was weakening. Around 8 p.m., we tried to get photos of the comet with each other in the frame, goofing around like a couple of kids, increasing the exposure time to gather as much light as possible. Our attempts were somewhat successful, though our bodies and faces are a bit grainy in the photographs. Still, that’s how we documented the event last week.

At 8:30 p.m., as we got in the truck to drive home, I looked up at the sky and said, “Goodbye, traveler. Thank you for the show.”

And that was that — so we thought.

“There may be another comet visible this week,” my husband said. “They are calling it the Halloween comet, and it may be as bright as Venus — unless it breaks up.”

I smiled, and these two old science nerds were suddenly filled with excitement again.

Amber sees the comet that will not be visible for another 80,000 years as it hurls through space. She says, “It is like laying our eyes on a rare and precious gem — a marvel.”

out of

Posted on